This post was written with assistance from generative AI. Read about my commitment to AI transparency here.

Introduction: The Most Famous Romantic Poets of All Time

Love speaks its most profound truths through the lessons it teaches us.

And when we can't make sense of what it's attempting to say, we turn to the universal language of love: poetry.

Across centuries and continents, poets have transformed passion into verse, capturing the human heart's wildest yearnings with words that still resonate today.

From ancient Greece to modern South America, these masters of romantic expression have not merely described love—they've reimagined it, elevated it, and given it a voice that echoes through time.

Their poetic achievements have woven themselves into our cultural fabric.

We quote Shakespeare at weddings, transcribe Neruda in love letters, and seek solace in Sappho's fragments when our hearts break.

These aren't just beautiful words—they're emotional blueprints that have shaped how civilization understands romance itself.

Join me on an intimate journey through the lives and works of history's most celebrated romantic poets.

We'll travel from Sappho's sun-drenched Lesbos to Neruda's sensual Chile, exploring how each poet's unique vision of love reflected their era while transcending it.

These are the artists who dipped their pens in their own blood and tears, creating verses that continue to illuminate love's mysteries for new generations.

PSST.... Hey Modern Romanticists & Art Lovers...

Receive Your Own Archival-Grade Modern Art Print From The Unreleased "Romantic Modernism" Collection At A Full 100% Discount

>>>Click Here If You're Interested<<<

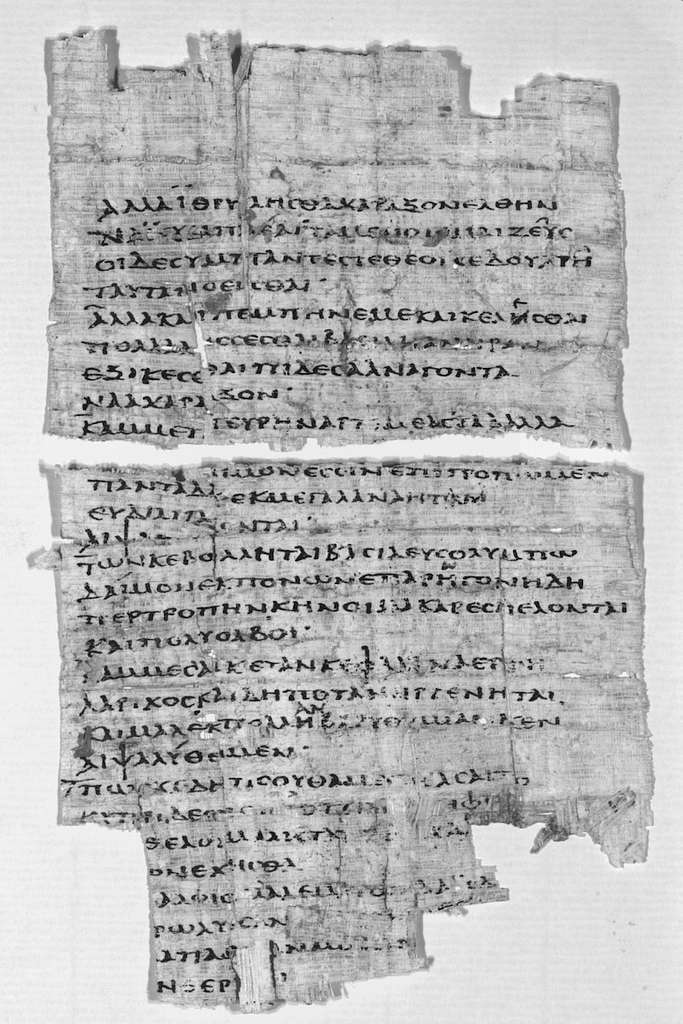

Sappho (c. 630 – c. 570 BCE)

Our journey begins nearly 2,600 years ago on the rocky shores of Lesbos, where Sappho—history's first great love poet—composed lyrics of such piercing emotion that Greeks called her the "Tenth Muse."

Today, only fragments remain of her nine volumes of poetry, each surviving piece a tantalizing glimpse of her genius.

Sappho transformed Greek poetry by turning away from epic tales of heroes to focus on personal emotion.

Writing in her native Aeolic dialect, she created new musical patterns for her verses, which were meant to be sung accompanied by the lyre.

Her innovations weren't merely technical—she brought unprecedented intimacy to poetry, speaking of desire with startling directness.

Her famous Fragment 31 captures love's physical overwhelm with astonishing precision:

"That man seems to me to be equal to the gods,

the man who sits opposite you

and listens nearby

to your sweet voice

and lovely laughter –

that indeed has stirred up the heart in my breast.

For whenever I look at you even briefly,

it is no longer possible for me to speak;

my tongue has snapped, at once a subtle

fire has stolen beneath my flesh,

I see nothing with my eyes,

my ears hum,

sweat pours from me, a trembling

seizes me all over, I am paler

than grass, and it seems to me that I am little short of dying."

With extraordinary psychological insight, Sappho maps love's assault on the body—the stilled tongue, racing heart, ringing ears.

This isn't abstract sentiment but physical reality, the visceral transformation that occurs when desire overwhelms reason.

In just sixteen lines, she articulates what neuroscientists now confirm: romantic love physically alters our perception and bodily functions.

Sappho's frank expressions of desire for women revolutionized poetic possibilities.

In an era when female voices were scarce in literature, she celebrated female beauty and love with unapologetic passion. Her poems to her female companions opened emotional and artistic doors that had previously been closed.

Though medieval Christian authorities burned much of her work in horrified censorship, Sappho's surviving fragments proved powerful enough to inspire two millennia of poets.

Her name gave us the terms "lesbian" and "sapphic," and her emotional honesty created a template for love poetry that values authenticity above all. Poets from Catullus to Keats have claimed her as their muse, and contemporary LGBTQ poets honor her as their artistic foremother.

Catullus (c. 84 - c. 54 BCE)

Several centuries after Sappho, in Rome's tumultuous final Republican days, Gaius Valerius Catullus crafted love poetry of unprecedented psychological complexity.

His cycle of poems addressing "Lesbia" (a literary pseudonym for the aristocrat Clodia Metelli) chronicles a passionate affair from its euphoric beginning through bitter heartbreak to smoldering resentment.

Catullus perfected what would become a hallmark of great love poetry: absolute emotional transparency. His verses to Lesbia swing between tender adoration and raw jealousy, between erotic celebration and wounded pride.

Unlike his more formal Roman contemporaries, Catullus wrote in a conversational style that feels startlingly modern—as if overhearing a lover's private thoughts.

His Poem 5 embraces love's urgent carpe diem, beginning:

"Let us live, my Lesbia, and let us love,

and let us value the tales of austere old men

at a single penny.

Suns may set, and suns may rise again:

but when our brief light has set,

night is one long everlasting sleep."

The poem captures youthful passion's defiance of mortality. Catullus urges his lover to seize pleasure while they can—to exchange "a thousand kisses, then a hundred"—because death will eventually claim them. His verses transform fleeting desire into a philosophical stance against time itself.

But unlike poets who idealize love, Catullus also explores its destructive power. His most famous couplet, from Poem 85, crystallizes love's contradictions:

"I hate and I love. Why I do this, perhaps you ask.

I know not, but I feel it happening and I am tortured."

This emotional honesty—capturing love's simultaneous pleasure and pain—revolutionized romantic poetry.

Catullus taught subsequent poets that authenticity matters more than flattering portraits of noble sentiments.

His willingness to reveal love's uglier emotions—jealousy, obsession, vindictiveness—expanded what love poetry could express.

By documenting a complete romantic lifecycle, from infatuation through disillusionment to bitter aftermath, Catullus created a template for the confessional love poem that still influences songwriters and poets today.

His verses remind us that great love poetry doesn't just celebrate romantic ideals—it explores love's full emotional spectrum, including its shadows.

Dante Alighieri (c. 1265-1321)

Our journey now carries us to medieval Florence, where Dante Alighieri transformed romantic devotion into spiritual transcendence.

His lifelong adoration of Beatrice Portinari—whom he met briefly at age nine, glimpsed occasionally throughout his youth, and mourned after her early death—inspired poetry that elevated human love to cosmic significance.

Dante didn't merely love Beatrice; he spiritualized her. In La Vita Nuova (The New Life), his collection of love poems interspersed with autobiographical prose, he recounts how seeing Beatrice transformed him, awakening virtues and inspiring his poetic voice.

His devotion becomes almost religious, with Beatrice as an earthly manifestation of divine love.

But it's in The Divine Comedy that Dante most profoundly elevates romantic love. After guiding the poet through Hell and Purgatory, Virgil departs, and Beatrice appears as Dante's guide through Paradise.

Transformed from earthly beloved to spiritual guide, she leads him toward ultimate understanding of divine love. As Dante writes:

"Here the holy face shone on me directly,

which, full of grace, gently glanced at me,

saying: 'Turn and listen; not in my eyes alone is Paradise."

Dante revolutionized love poetry by connecting romantic feeling to spiritual evolution. For him, Beatrice wasn't just a beautiful woman but a catalyst for moral and spiritual growth.

His love for her becomes a stepping stone toward divine understanding, a path toward enlightenment rather than merely sensual or emotional fulfillment.

This transformation of courtly love into spiritual journey reshaped Western conceptions of romance. Dante suggested that love's highest purpose wasn't physical union or even mutual affection, but the beloved's capacity to inspire virtue and spiritual awakening in the lover.

His poetry taught that human love, when properly understood, points toward divine love.

Through Dante, romantic poetry acquired a profound metaphysical dimension. His verses didn't just describe attraction or desire but reimagined love as a cosmic force connecting human experience to divine reality. His influence echoes through centuries of poets who sought to find transcendent meaning in romantic experience.

Petrarch (1304-1374)

If Dante spiritualized love, Francesco Petrarca—known as Petrarch—perfected its poetic expression.

This 14th-century Italian scholar and poet created the most influential model for love poetry in Western literature: the Petrarchan sonnet sequence.

His Canzoniere (Songbook), containing 366 poems mostly dedicated to his unattainable beloved Laura, established conventions that would dominate European love poetry for centuries.

Petrarch reportedly glimpsed Laura in the Church of Saint Clare in Avignon on April 6, 1327—a moment that launched a lifelong poetic obsession, though they never established a relationship.

His sonnets trace the emotional journey of unrequited love, from initial awestruck admiration through passionate longing to spiritual reflection after Laura's death.

His innovation lay in structuring the 14-line sonnet to mirror love's psychological progression. The octave (first eight lines) typically presents a problem or situation; the sestet (final six lines) offers a resolution or reflection.

This formal pattern perfectly captures love's tensions and contradictions. As he writes:

"Love found me disarmed, and the way open

through my eyes to my heart, my eyes that are now the portal and passageway to tears:

so that it seems to me it does him little honor

to wound me with an arrow now, in that state,

he not showing his bow at all to you who are armed."

Petrarch's sonnets established tropes that would become the language of romantic poetry: love as warfare, love as sickness, the beloved as both torturer and savior.

He perfected the paradoxical expressions—"sweet pain," "freezing fire"—that capture love's contradictory nature. His Laura became the prototype for the idealized, unattainable beloved who inspires from a distance.

His technical innovations matched his psychological insights. Petrarch refined the sonnet form, creating intricate patterns of sounds and images that mirror love's complex emotions.

His verses move with musical precision, each line building toward emotional climaxes that feel simultaneously carefully crafted and spontaneously felt.

Petrarch's influence cannot be overstated.

His sonnets created a vocabulary of romantic expression that spread throughout Renaissance Europe, inspiring imitations in French, Spanish, and eventually English. Every subsequent sonneteers, including Shakespeare, wrote in dialogue with Petrarch, either following his model or deliberately breaking from it.

His conception of love as simultaneously painful and ennobling shaped Western romantic ideals for generations.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

When love's language reached England's shores, it found its supreme master in William Shakespeare.

Already revolutionizing drama, Shakespeare turned his unparalleled linguistic gifts to the sonnet, producing 154 poems that transformed Petrarch's innovations into something distinctly English—and distinctly Shakespearean.

Shakespeare's sonnets, published in 1609, broke new ground in both form and content.

He modified the Petrarchan sonnet into what we now call the Shakespearean sonnet, with three quatrains and a concluding couplet, creating a more flexible structure for exploring love's complexities.

Within this structure, he expanded the emotional range of love poetry, addressing desire, jealousy, infidelity, aging, and mortality with unprecedented psychological depth.

Most revolutionary was Shakespeare's rejection of idealized love.

His sonnets to the "Fair Youth" and "Dark Lady" present relationships filled with doubts, power struggles, and conflicting emotions. In Sonnet 116, he famously defines love as "an ever-fixed mark / That looks on tempests and is never shaken," but elsewhere acknowledges how rarely actual relationships achieve such constancy.

Sonnet 18 begins with perhaps the most famous comparison in English poetry:

"Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer's lease hath all too short a date:"

What appears initially as conventional praise evolves into a profound meditation on mortality and art's power to preserve beauty.

Shakespeare promises immortality through poetry—"So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see, / So long lives this, and this gives life to thee"—suggesting that love poetry transcends both the lover and beloved, preserving their connection for future generations.

Shakespeare's genius lay in combining metaphysical insight with emotional authenticity.

His sonnets explore love's philosophical dimensions while remaining grounded in lived experience.

He maps love's contradictions—its simultaneous selfishness and selflessness, its blend of physical desire and spiritual connection—with unmatched precision.

By addressing sonnets to both male and female beloveds, Shakespeare also expanded love poetry's scope beyond conventional heterosexual romance.

His sonnets to the Fair Youth express tenderness, admiration and jealousy with the same emotional intensity as those to the Dark Lady, suggesting that deep attachment transcends gender categories.

Shakespeare's love poetry transformed the genre by prioritizing truth over idealization.

He showed that authentic romantic expression could embrace love's imperfections, disappointments, and moral complexities.

His influence reverberates through every subsequent English-language poet who attempts to capture love's mysteries.

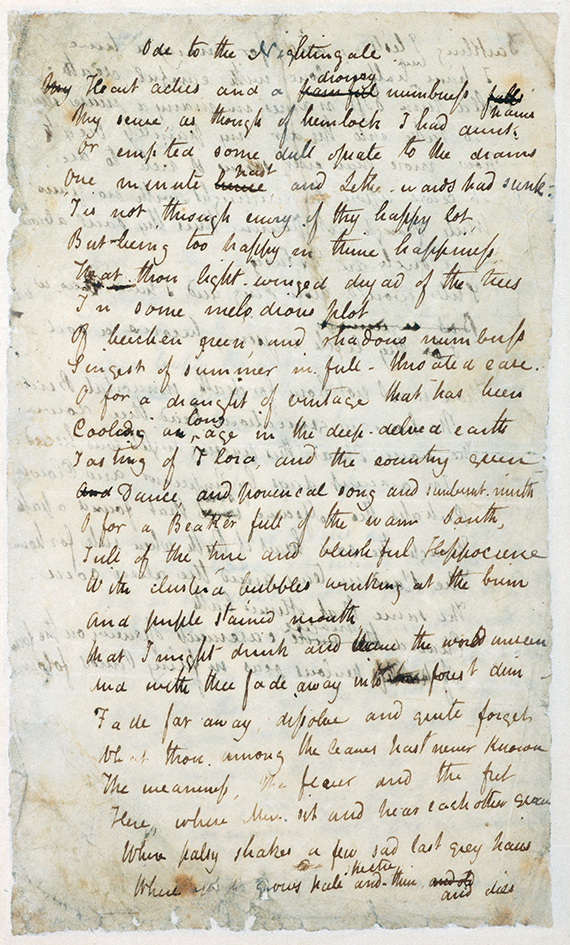

John Keats (1795-1821)

The Romantic era brought fresh passion to love poetry, and no poet captured romantic love's sensual intensity more powerfully than John Keats.

Though his life was tragically brief—he died of tuberculosis at just 25—Keats created love poems of extraordinary beauty, blending classical imagery with visceral emotion and philosophical depth.

Keats's approach to love poetry emerged from his concept of "negative capability"—the capacity to remain in "uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason."

This openness to experience, rather than intellectual analysis, suffuses his romantic verses with immediate sensory power.

His poems don't describe love; they recreate its physical and emotional sensations.

His romance with Fanny Brawne inspired some of his most moving love poems.

Engaged but unable to marry due to his illness and financial instability, Keats channeled his frustrated passion into verses that pulse with desire and mortality's shadow.

"Bright Star" exemplifies this tension:

"Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art—

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature's patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth's human shores"

The poem juxtaposes the star's eternal detachment with the poet's desire for constant connection with his beloved. Keats longs for the star's permanence but not its isolation—he wishes to remain "still stedfast" but "pillow'd upon my fair love's ripening breast."

The contrast captures love's fundamental paradox: the desire for both timelessness and physical intimacy.

Keats revolutionized love poetry by infusing it with heightened sensuality.

His verses engage all five senses, creating an almost synesthetic experience where touch, taste, sound, scent and vision blur together in ecstatic communion.

When he addresses Fanny in "The day is gone, and all its sweets are gone," readers don't just understand his longing—they feel it physically.

Yet Keats's romantic verses transcend mere sensuality. His letters to Fanny reveal how deeply he understood love's transformative power: "I have been astonished that Men could die Martyrs for religion—I have shuddered at it—I shudder no more—I could be martyred for my Religion—Love is my religion—I could die for that."

For Keats, love wasn't just emotion but a complete worldview, a spiritual framework giving meaning to existence.

By connecting romantic love to life's most profound questions—beauty, time, mortality, transcendence—Keats elevated the love poem from personal sentiment to philosophical exploration.

His verses remind us that authentic passion inevitably confronts life's deepest mysteries and can illuminate them more clearly than rational inquiry alone.

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)

While Keats explored love's sensual dimensions, his contemporary Percy Bysshe Shelley approached romance through its metaphysical implications.

Shelley's love poetry transforms personal attachment into cosmic principle, suggesting that romantic connection reveals fundamental truths about existence itself.

Though remembered primarily for political poetry and literary theory, Shelley produced love poems of extraordinary philosophical power. His verses suggest that genuine love transcends individual personalities, connecting lovers to universal forces that animate all creation.

This approach reflects his broader philosophical interests in Platonism and pantheism.

"Love's Philosophy," perhaps his most widely anthologized love poem, exemplifies this cosmic perspective:

"The fountains mingle with the river

And the rivers with the ocean,

The winds of heaven mix for ever

With a sweet emotion;

Nothing in the world is single;

All things by a law divine

In one spirit meet and mingle.

Why not I with thine?—"

Shelley transforms romantic desire into natural principle.

The poem's simple, musical verses draw parallels between human longing and cosmic patterns, suggesting that love fulfills nature's fundamental tendency toward connection and unity.

Romance becomes not merely personal preference but participation in universal law.

This elevation reaches its apex in "Epipsychidion," Shelley's 600-line poem addressed to Emilia Viviani, a young Italian woman confined to a convent.

Beyond expressing personal attraction, the poem develops an elaborate philosophical system in which perfect love transcends individual identity:

"We shall become the same, we shall be one

Spirit within two frames, oh! wherefore two?

One passion in twin-hearts, which grows and grew,

Till like two meteors of expanding flame,

Those spheres instinct with it become the same,

Touch, mingle, are transfigur'd; ever still

Burning, yet ever inconsumable"

For Shelley, genuine love dissolves boundaries between self and other, creating mystical union that resembles religious transcendence.

His lovers don't merely complement each other but merge into higher spiritual reality, their individual personalities transformed through mutual devotion.

This metaphysical approach to romance reflects Shelley's revolutionary temperament.

Just as he imagined radical political transformation, he envisioned love as force for personal transfiguration.

His romantic relationships—often unconventional by contemporary standards—attempted to embody these ideals, though reality frequently fell short of his poetic vision.

Shelley's influence extended beyond poetry into cultural attitudes about romantic love. His conception of romance as transformative spiritual experience, transcending social convention and individual limitation, helped establish the Romantic era's elevation of passion above reason.

For better and worse, his vision of love as quasi-religious experience continues to shape Western romantic ideals.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861)

The Victorian era brought new voices to love poetry, none more influential than Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

Her masterwork, Sonnets from the Portuguese—written during her courtship with poet Robert Browning and published in 1850—reinvigorated the sonnet tradition by bringing authentic female perspective to a form historically dominated by male voices.

Barrett Browning's path to poetic prominence was remarkable. Confined to her bedroom for years by mysterious illness and controlling father, she built literary reputation through correspondence with prominent writers.

When Robert Browning initiated contact after admiring her work, their literary exchange blossomed into romance, eventually culminating in secret marriage and elopement to Italy, where Elizabeth's health dramatically improved.

The 44 sonnets chronicling their courtship remain among the most beloved love poems in English literature.

Unlike earlier sonneteers who addressed imaginary or unattainable beloveds, Barrett Browning wrote about real, reciprocal love developing toward marriage.

Her most famous sonnet begins:

"How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace."

These lines revolutionized love poetry through their directness.

Without elaborate conceits or classical allusions, Barrett Browning articulates love's emotional dimensions with striking clarity. She continues, "I love thee freely, as men strive for right; / I love thee purely, as they turn from praise," grounding romantic feeling in moral authenticity rather than courtly display.

Barrett Browning brought unprecedented psychological realism to romantic verse.

Her sonnets acknowledge doubt, fear, and unworthiness alongside devotion.

Unlike poets who present love as immediate certainty, she traces its gradual evolution, recording moments when "the first time that the sun rose on thine oath / To love me, I looked forward to the moon / To slacken all those bonds which seemed too soon / And quickly tied to make a lasting troth."

By focusing on mutual love rather than idealized adoration from afar, Barrett Browning expanded love poetry's emotional range.

Her verses celebrate partnership, reciprocity, and shared spiritual growth rather than conquest or worship.

When she declares, "I love thee with the breath, / Smiles, tears, of all my life," she acknowledges love's integration into daily existence, not just passionate moments.

Barrett Browning also reclaimed religious imagery for authentic romantic expression. Victorian convention often separated spiritual devotion from erotic attachment, but her sonnets suggest these impulses intertwine.

She concludes her most famous sonnet with "I shall but love thee better after death," suggesting that genuine human love participates in eternal spiritual reality.

As one of the era's most successful female poets, Barrett Browning helped open literary doors for women's romantic expression.

Her unflinching emotional honesty, combined with technical mastery, demonstrated that feminine perspective could enrich rather than diminish poetic tradition.

Her influence reverberates through subsequent generations of women poets who found their authentic voices in love's complex emotional landscape.

Pablo Neruda (1904-1973)

Our poetic journey concludes with Pablo Neruda, the Chilean Nobel laureate whose sensual, imagistic love poems revolutionized 20th-century romantic expression.

Neruda liberated love poetry from Victorian restraint, infusing it with direct eroticism, surrealistic imagery, and political consciousness that spoke to modern experience.

Born Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto in southern Chile, Neruda adopted his pen name as a teenager.

His early collection Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair (1924), published when he was just twenty, stunned the Spanish-speaking world with its frank sexuality and emotional intensity.

These poems, still among his most widely read, celebrate physical passion without euphemism or apology.

In Love Poem XIV, Neruda writes:

"My words rained over you, stroking you.

A long time I have loved the sunned mother-of-pearl of your body.

Until I even believe that you own the universe.

I will bring you happy flowers from the mountains, bluebells, dark hazels, and rustic baskets of kisses.

I want to do with you what spring does with the cherry trees."

This final line—one of poetry's most memorable expressions of desire—captures Neruda's gift for transforming physical longing into natural metaphor.

Unlike earlier poets who spiritualized passion, Neruda grounds love in bodily experience while simultaneously expanding it through vivid imagery drawn from landscape, season, and elemental forces.

Neruda's love poetry evolved throughout his life, reflecting his changing circumstances and political consciousness.

His later collections, particularly The Captain's Verses and One Hundred Love Sonnets, written for his third wife Matilde Urrutia, interweave personal devotion with awareness of social struggle and cosmic perspective.

In Sonnet XVII, he writes:

"I love you without knowing how, or when, or from where,

I love you directly without problems or pride:

I love you like this because I don't know any other way to love,

except in this form in which I am not nor are you,

so close that your hand upon my chest is mine,

so close that your eyes close with my dreams."

Here Neruda suggests that genuine love transcends individual identity, creating union that dissolves boundaries between self and other.

He grounds transcendence in physical intimacy—"your hand upon my chest is mine."

Neruda revolutionized love poetry through his surrealistic imagery, which connects romantic emotion to unexpected objects and sensations.

In Sonnet XI, he writes, "I crave your mouth, your voice, your hair. / Silent and starving, I prowl through the streets. / Bread does not nourish me, dawn disrupts me, all day / I hunt for the liquid measure of your steps."

This blending of physical desire with dreamlike perception creates a new language for love's disorienting effects.

While celebrating love's raptures, Neruda never flinches from its darker dimensions. The "song of despair" that concludes his early collection acknowledges loss and abandonment.

Later works explore jealousy, absence, and mortality. His poetic range embraces love's entire emotional spectrum, from ecstatic communion to desolate longing.

Neruda's global influence derives partly from his accessibility. Despite sophisticated technique, his love poems speak in direct voice that resonates across cultural boundaries.

His verses have been translated into dozens of languages, inspiring generations of lovers who find their own experiences reflected in his passionate declarations and sensual metaphors.

A Legacy of Passion

From Sappho's fragments to Neruda's sonnets, the world's greatest love poets have transformed private feeling into universal art.

They haven't merely described romantic experience but elevated it, revealing how personal attachment connects to life's deepest mysteries—time, beauty, mortality, transcendence.

Each poet channeled love through cultural frameworks of their era while simultaneously expanding those frameworks.

Sappho brought unprecedented psychological insight to ancient Greek expressions of desire.

Dante transformed courtly love into spiritual journey.

Shakespeare infused conventional sonnet forms with emotional complexity that transcended convention.

Barrett Browning brought female perspective to Victorian literary tradition.

Neruda connected erotic passion to political consciousness and surrealistic perception.

The impact of these poetic visions extends far beyond literature. Their verses have shaped how cultures conceptualize romance itself.

When Petrarch portrays love as sweet suffering that ennobles the soul, he establishes romantic paradigm that influences centuries of European thought.

When Keats connects desire to beauty and mortality, he suggests that romantic attachment offers unique access to life's essential truths.

Great love poetry doesn't just express emotion but creates framework for understanding it.

When Catullus writes "I hate and love" or Shakespeare observes that "love is not love / Which alters when it alteration finds," they offer emotional wisdom that helps readers navigate their own romantic experiences. Their verses become reference points for understanding love's contradictions and complexities.

This explains why romantic poetry maintains such cultural presence.

We quote these poets in wedding ceremonies, inscribe their verses in Valentine's cards, turn to their wisdom when our hearts overflow or break. Their words articulate what we feel but cannot express, giving shape to emotions that might otherwise remain formless.

The enduring power of great love poetry reminds us that romantic experience transcends historical and cultural boundaries.

When modern readers feel Sappho's physical symptoms of desire or recognize themselves in Neruda's metaphors, they experience fundamental continuity of human emotion across millennia.

These poets speak universal language of the heart.

As long as humans continue falling in and out of love, we will need poets to help us understand what happens when we do. The tradition these masters established—transforming private feeling into shared artistic experience—continues in contemporary poetry, song lyrics, and new forms of expression. Their legacy reminds us that love, despite its mysteries and contradictions, remains our most profound connection to each other and to life's essential meaning.

PSST.... Hey Modern Romanticists & Art Lovers...

Receive Your Own Archival-Grade Modern Art Print From The Unreleased "Romantic Modernism" Collection At A Full 100% Discount

>>>Click Here If You're Interested<<<